Click here for a very interesting (and quite lengthy)article on Chinese adoption

Here's some excerpts if you don't have time to read the whole thing:

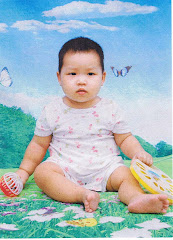

“In June 2004 at a hotel in Changsha, a caretaker from the Hengshan County Children’s Welfare Institute handed my wife and me a 17-month-old girl the orphanage had named She Mei Chun. We stayed in China for another week or so after that, filling out forms, going to appointments, and getting to know our new daughter. In case of trouble while we traipsed around Changsha and Guangzhou, we had a note in Chinese, supplied by the U.S. adoption agency that had brought us and 18 other couples to China, informing suspicious bystanders that we were adopting Mei, not kidnapping her. It wasn’t necessary. China sends thousands of baby girls abroad every year, and people in the places we visited were accustomed to seeing Americans and other foreigners walking around with children to whom they clearly are not biologically related….”

“In 2006 about 6,500 Chinese girls were adopted by Americans. Roughly the same number were adopted by people in other Western countries, including Canada, Spain, Germany, France, and the U.K. But these 13,000 girls were just a fraction of China’s abandoned children, the vast majority of whom are female. The Chinese government has estimated there are 160,000 orphans in China at any given time; in her 2000 adoption memoir The Lost Daughters of China, California journalist Karin Evans notes that human rights activists say the number of orphans “is undoubtedly far higher—perhaps ten times the official count, or more.” Between a government that is not known for its openness and outside observers who are forced to guesstimate (and who may have their own reasons for exaggerating), the relevant figures are maddeningly hard to pin down…”

“The Hunan orphanage encouraged visits, and my wife, Michele, went there along with several other parents. She found it to be clean though spartan, and better staffed than she had imagined, with two caretakers per room, each of which contained eight single-occupancy cribs. More important, the caretakers, who cried upon relinquishing their charges at the hotel in Changsha, clearly were very attached to the girls, and vice versa. (Further testimony to the strength of this relationship: Mei, who evidently did not understand the note that said we were not kidnapping her, screamed for hours before I was able to distract her with toys, and she refused to let Michele hold her until after we returned to the U.S.) The Guangdong orphanage, by contrast, did not allow visits, which probably is not a good sign…”

“Chinese officials may even be having second thoughts about international adoptions, which account for a small portion of abandoned girls but contribute (slightly) to the gender imbalance and could be seen as indirectly encouraging over-quota births. The number of Chinese babies adopted by Americans peaked at nearly 8,000 in 2005, falling to 6,500 last year…According to The New York Times, “The restrictions are in response to an enormous spike in applications by foreigners, which has far exceeded the number of available babies.” Since the number of Chinese children who need parents at any given time ranges somewhere between 160,000 (per the government) and 1.6 million (per human rights groups), it seems the demand exceeds the supply only because the government has arbitrarily decided that a small fraction of the children are “available.”

“Something else I didn’t anticipate was how wrenching the experience of taking Mei from her caretaker would be. Our first daughter, also adopted and now 14, was born in Brooklyn and came to live with us when she was 3; she spoke English and had already gotten to know us. In Mei’s case, I did not give sufficient thought to what a terrifying trauma it is for a 17-month-old to be taken from the only home she’s ever known, separated from the women who have been raising her, and peremptorily handed over to complete strangers who look, smell, and sound different from anything to which she’s accustomed. Although we were anxious about the first meeting, we thought of it as a happy occasion, because that’s what everyone else seemed to expect. Instead, it was a heart-breaking scene: 10 families crammed into a conference room with 10 screaming toddlers who had no means of preparing for this baffling betrayal.

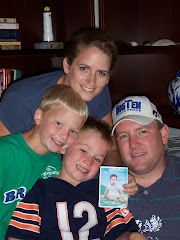

Mei cried for hours and remained subdued for weeks. One exception occurred when she saw She Mei Yi, who had slept in the crib next to hers at the orphanage, in a hotel restaurant a day or two after the handoff. Both girls’ faces lit up as they lunged for each other, as if to say, “I thought I’d never see you again!” Then they began enthusiastically biting and slapping each other—their way of expressing affection.

During a recent trip to Boston, where Mei Yi now lives, Mei was again reunited with her former crib neighbor. Although they were soon playing happily together and looking forward to future visits, the meeting was much less dramatic than the encounter at the hotel in Changsha. The two girls, now 4 years old, did not remember their early connection as much as their parents’ stories about it, and they were no longer desperate to see a familiar face. But I don’t want to forget the joyful relief of that first reunion, which reflected the misery caused by government policies that break up families and disrupt young lives. As grateful as I am for the opportunity to see Mei every day and watch her grow up, I realize that in a better world we never would have met.”

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment